New Testament studies

Acts as context for the early church and Paul’s letters.

The Book of Acts provides important context for understanding the early church and the missionary activity of the Apostle Paul. Luke begins Acts where the Gospel of Luke ends—with a resurrected Jesus teaching his disciples. In the subsequent chapters Luke describes the pouring out of the Spirit and the expansion of the early church throughout the Mediterranean region. The apostle Paul plays a key role in this expansion through a series of missionary journeys, which are described in the second half of Acts. During these journeys Paul starts new churches in cities like Corinth, Philippi, and Thessalonica–churches that he later writes letters to. These letters make up a large portion of the New Testament, and Acts provides the context for many of these letters. While it is difficult to synchronize exactly the descriptions in Acts with Paul’s letters, Acts provides a general timeline for the early church and many of the NT writings.

From the events in Acts, we can arrive at a general timeline for the early church and the apostle Paul. However, there are two particularly debated issues that affect any more detailed timeline; those issues are: 1) Do the time periods mentioned in Galatians 1:18 (3 years) and 2:1 (14 years) overlap, or are they sequential (not to mention Gal 1:17 states Paul went to Arabia after his conversion, something Acts does not mention)? 2) Does Paul’s trip to Jerusalem, described in Galatians 2, match Acts 11:27-30 or Acts 15? With these issues in mind (as well as uncertainty whether Jesus was crucified in A.D. 30 or 33), here is a possible timeline (borrowed from Darrell Bock’s Acts commentary) for the early church based on Acts:

| Date | Event | Reference | Paul’s Letters |

| AD 33 | Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection | 4 Gospels; Acts 1 | |

| 50 days after resurrection | Pentecost and the pouring out of the Holy Spirit | Acts 2 | |

| AD 34 | Martyrdom of Stephen, scattering of the church from Jerusalem, Paul’s conversion | Acts 7-9 | |

| AD 48-49 | First missionary journey | Acts 13-14 | |

| AD 49/50 | Jerusalem Council | Acts 15:1-35 | Galatians (shortly before council) |

| AD 50-52 | Second Missionary Journey | Acts 15:36-18:22 | 1-2 Thessalonians |

| AD 53-57 | Third Missionary Journey | Acts 18:23-21:16 | 1-2 Corinthians, Romans |

| AD 57-59 | Paul’s arrest and imprisonment | Acts 21:27-26:31 | |

| AD 59-61 | Paul’s journey and imprisonment in Rome | Acts 27-28 | Philippians, Colossians, Ephesians, Philemon |

| AD 62-63 | Paul’s release from prison and trip to Spain | Romans 15:24, 28; 1 Clement 5:5–7 | 1 Timothy |

| AD 64-66 | Paul’s imprisonment and execution in Rome | 2 Timothy 1:8; 4:6–8: Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 2.22 | Titus, 2 Timothy |

Paul’s missionary activity is followed in a more detailed way throughout Acts. The following paragraphs summarize and follow Paul’s journeys in text and in maps.

First missionary journey.

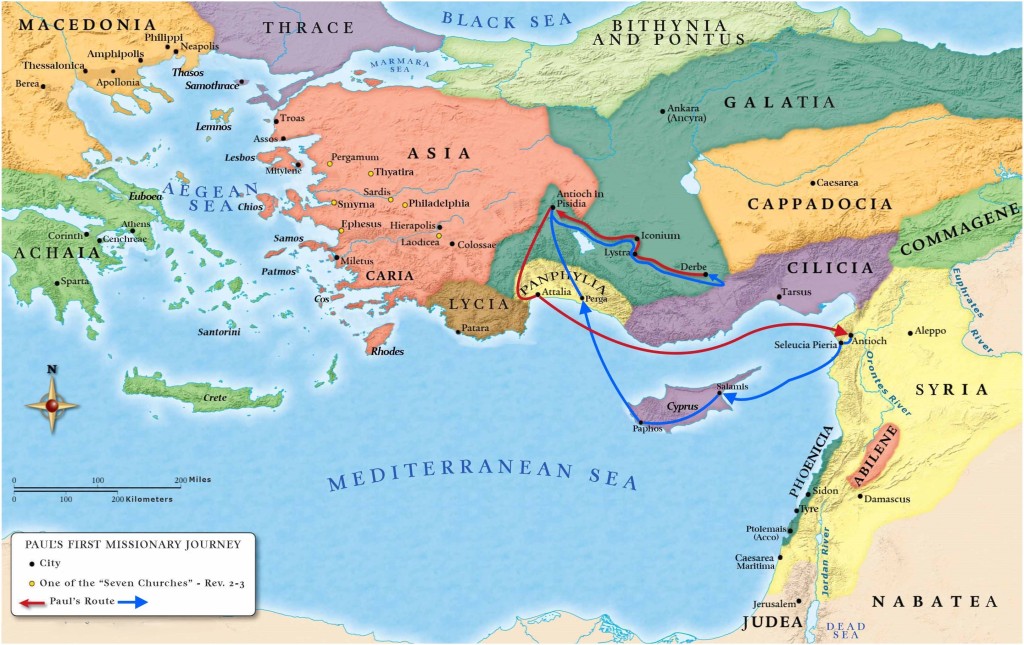

Paul’s first missionary journey is described in Acts 13:1–14:28. The Holy Spirit calls the church in Antioch to “set apart for me Barnabas and Saul for the work to which I have called them.” After fasting and prayer, the church sends out Paul and Barnabas (who also take along John Mark). The journey followed the following route:

After leaving Antioch (Acts 13:1–3), they travel to Seleucia (Acts 13:4) to Salamis (Acts 13:5) to New Paphos (Acts 13:6–12) to Perga of Pamphylia (Acts 13:13; John Mark leaves the mission) to Antioch of Pisidia (Acts 13:14–52) to Iconium (Acts 14:1–7) to Lystra (Acts 14:8–20) to Derbe (Acts 14:20). After Derbe, Paul and Barnabas double back to visit the same towns again and appoint elders in Lystra, Iconium, and Pisidian Antioch (Acts 14:21–23). They then travel to Perga and Attalia (Acts 14:25) and finally back to Antioch (Acts 14:26–28).

________________________________________________

Second missionary journey.

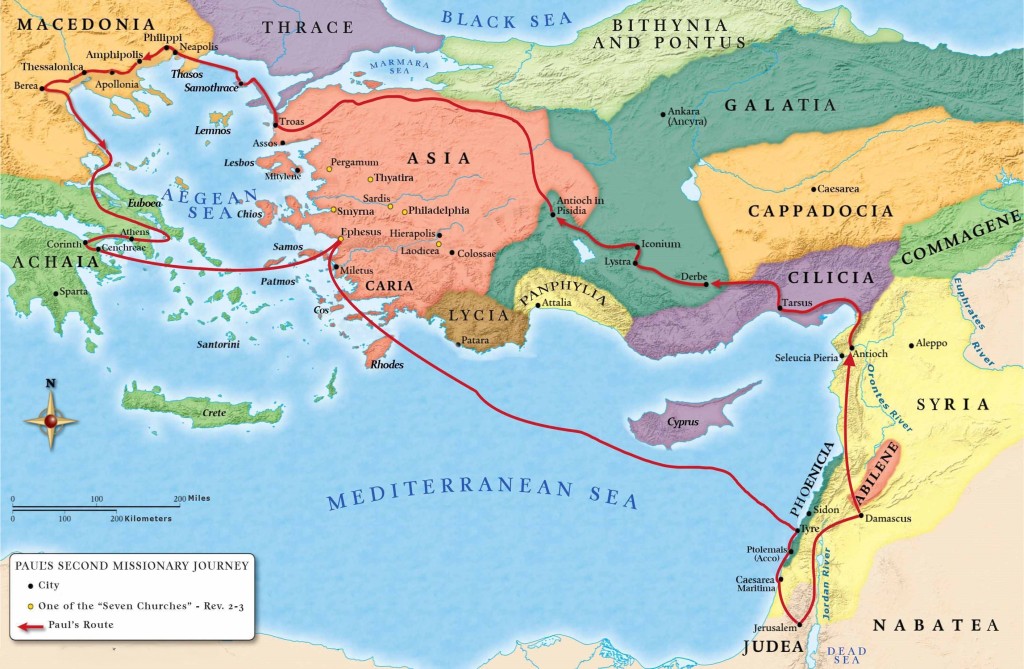

Paul’s second missionary journey is recorded in Acts 15:36–18:22. Shortly after the Jerusalem council, Paul and Barnabas decide to return and visit the churches in every city where they had proclaimed the word of the Lord (Acts 15:36). Paul and Barnabas sharply disagree over taking John Mark with them again to the point that they part ways; Paul instead takes Silas with him, and Barnabas sails for Cyprus with John Mark.

Some of Paul’s most memorable encounters happen on this journey. In Lystra, Paul meets Timothy and invites him to join his missionary team (Acts 16:1-3). Timothy would be one of Paul’s most trusted fellow-workers (Rom 16:21; 1 Cor 4:17; Phil 1:1; Col 1:1; 1 Thes 1:1; Philemon 1:1; 1-2 Timothy). Passing through Asia to Troas, Paul receives a vision of a man from Macedonia calling him to cross the Aegean sea. Soon after, Paul and his companions set sail for the Macedonian region (Acts 16:8-10). In Philippi, Paul casts a fortune telling spirit out of a slave girl, which enrages her masters to the point they get Paul and Silas put in jail (Acts 16:16-24). An earthquake from the Lord frees Paul and Silas who choose to witness to the jailer rather than flee (Acts 16:25-40). After further travel, Paul eventually arrives in the Greek city of Corinth and spends about a year a half there. Paul most likely wrote his two letters to the church of Thessalonica during this stay at Corinth. Paul also meets Priscilla and Aquila, who become a trusted ministry couple for years to come (Acts 18:18-26; Rom 16:3; 1 Cor 16:19; 2 Tim 14:9).

The second missionary journey went along the following route: After leaving Antioch, Paul and Silas travel to Syria and Cilicia (Acts 15:41) to Derbe and Lystra (Acts 16:1–5) through the Phyrgian and Galatian region (Acts 16:6) to Mysia (Acts 16:7–8) to Troas (Acts 16:8–10). By boat they went to Samothrace (Acts 16:11) and on to Neapolis (Acts 16:11). Once again on land, they travelled to Philippi (Acts 16:12–40; 1 Thess 2:2; Phil 4:15). They then went through Amphipolis and Apollonia (Acts 17:1) on the way to Thessalonica (Acts 17:1–9; 1 Thess 2:1–10; Phil 4:16) to Berea (Acts 17:10–14) to Athens (Acts 17:15–34; 1 Thess 3:1–6) to Corinth (Acts 18:1–17; 1 Cor 3:6). Paul then headed back by boarding a ship at Cenchrea (Acts 18:18) and sailed to Ephesus where he left Priscilla and Aquila (Acts 18:19–21) and then sailed on to Caesarea (Acts 18:22). From Caesarea, Paul and Silas probably went to Jerusalem before eventually returning to the church in Antioch.

__________________________________________________

Third missionary journey

Acts 18:23–21:16 describes Paul’s third missionary journey, which once again departs from Antioch. After encouraging the churches in Galatia and Phyrgia, Paul arrived in Ephesus, where he successfully ministered for about three years (Acts 19). Threats and violence from those who made idols of the goddess Artemis caused Paul to finally leave. During his stay in Ephesus, Paul most likely wrote his first letter to the Corinthians, and sometime later his second letter to the Corinthians in response to a report from Titus (2 Cor 7:6, 13; 8:16-23). From Ephesus, Paul visited Macedonia and went on to Greece. Paul stayed three months in Greece, mostly likely in Corinth the majority of the time where he wrote the epistle to the Romans. On the return trip to Jerusalem, Paul went through Macedonia again, visiting Philippi. After sailing from Troas to Miletus, the elders of the Ephesian church met with Paul for the last time (Acts 20:17-38). From there, Paul and his companions traveled to Caesarea by boat, making several stops along the way (Acts 21:1-8). After a short stay in Caesarea, Paul and others made the pilgrimage to Jerusalem for the feast of Pentecost and for Paul to fulfill his oath (Acts 21:15-26).

We can trace the third missionary journey through the following places: Paul and his companions went through Galatia and Phyrgia strengthening disciples (Acts 18:23) and on to Ephesus, where Paul stayed 3 years (Acts 19:1–40; 1 Cor 16:8). After the stay in Ephesus, they went through Macedonia strengthening the churches on their way to Corinth/Greece (Acts 20:2), where they stayed 3 months. As they headed back to Syria/Jerusalem they once again passed through Macedonia/Philippi (Acts 20:3–6a). From Philippi they sailed to Troas where Paul raised the boy who fell out a window (Acts 20:6b–12). They then sailed to Assos, Mitylene, Chios, Samos (Acts 20:13–15) and on to Miletus (Acts 20:16–38). After meeting with the Ephesian elders in Miletus, they sailed to Cos, Rhodes, Patara (Acts 21:1–2) and on to Tyre (Acts 21:3) to Ptolemais (Acts 21:7) to Caesarea (Acts 21:8–14) and finally to Jerusalem (Acts 21:15, 17–26).

______________________________________________________

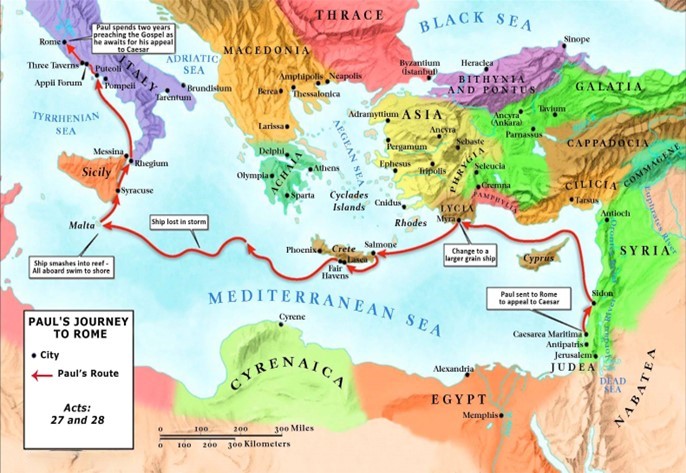

Journey to Rome

After his arrest for causing a disturbance in the temple, Paul remains in custody for at least two years awaiting trial. During this time, the Jewish leaders accuse and plot to kill Paul, and Paul makes several speeches and appeals before various Roman authorities (Acts 22:22-26:31). All these Roman authorities appear to consider Paul innocent, which may be the author’s way of showing Christianity’s harmlessness to Rome and its citizens. After appealing to Caesar during his trial before the governor Festus (Acts 25:11-12), Paul begins his journey to Rome. The mostly ocean voyage takes several months due to a shipwreck on the island of Malta. After finally arriving in Rome, Acts 28:30-31 states that Paul proclaimed the gospel without hindrance for two years as he awaited trial. The book of Acts ends with this statement of Paul’s bold proclamation of the gospel in Rome, which was a fitting fulfillment of Jesus’ commission (Acts 1:8) to be his witnesses to “the ends of the earth.” From his letter to the Philippians, we learn that Paul even had opportunity to spread the gospel among the imperial guards, and to Caesar’s household (Phil. 1:12-13; 4:22). In addition to his epistles to the Philippians, Paul also probably wrote his epistle to the Colossians, Ephesians, and to Philemon during his Roman imprisonment.

Very early tradition suggests that Paul was released after this imprisonment (1 Clement 5:5–7; Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 2.22) and continued even further west on another missionary journey. During this period of freedom, Paul probably wrote First Timothy and Titus. Not long after his release, Emperor Nero blamed the great Roman fire on Christians. A severe persecution broke out against the Christians, which probably resulted in Paul’s re-arrest and transfer to Rome. During this imprisonment Paul wrote his last letter—Second Timothy. Paul was most likely martyred by Nero sometime in AD 64-66.

___________________________________

End Notes

Bock, Darrell. Acts. BECNT; Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2007.

Lenski, R. The Interpretation of the Acts of the Apostles. Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1961.

Parsons, M. Acts. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008.

Schreiner, Patrick. Acts. Christian Standard Commentary. Holman Publishing, 2021.

Simeon’s Story: An exegetical retelling of Luke 2:25-39.

Preachers often assume that an exegetical presentation of a text requires the typical sermon format. However, one can present the meaning of a text, along with its historical and literary context, in other formats. Below is an example of an one person exegetical drama from the perspective of Simeon. You will notice that a lot of historical context is woven into Simeon’s speech as well as references to the most likely Old Testament allusions. Care was also taken to emphasize Luke’s most likely purpose in including the Simeon pericope in his Gospel.

The hermeneutical task includes presenting a text in a way that hearers can understand and apply. Certain hearers are better able to hear and apply a first-person presentation of an exegeted text. When preachers vary their presentation, they are more likely to reach a broader spectrum of listeners. I hope you find the following presentation of Luke 2:25-39 helpful to your preaching.

Simeon’s story. A historically based, first-person retelling of Luke 2:25-39

As I look back on my life, I see it has been a life of waiting. Even as a child, my father and I would scan the western horizon for clouds as we waited for the spring rains to refresh the land. He would say, “Simeon, don’t let the wait for rain dampen your spirits.” He told me that every new generation of Israelites must learn to wait on God. Our God announces something through his prophets, and it might take centuries for God’s promises to be fulfilled-but our God keeps His promises. Our ancestors waited in Egypt for 400 years before God raised up Moses to deliver them from slavery. My father assured me that one day God would send a savior whose kingdom will never end. He said, “The prophets have predicted it, so we can count on it. Until then we wait for God’s kingdom, and we don’t settle for a man-made substitute.”

I later understood that my father was speaking about the Jewish Hasmonaeans who claimed to be God’s chosen rulers. When I was a boy, Israel was actually independent. After the Maccabean revolt threw off foreign rule, many thought that the prophecies of restoration were fulfilled and the wait for Israel’s golden age was over. But eventually the Jewish kings were not much better than foreign ones, and infighting caused them to invite the Romans to come help. The problem is when the Romans help, they help themselves to whatever is best for Rome. When I was a young man just starting on my own, the Romans marched into Jerusalem. We are still waiting for them to leave.

I later understood that my father was speaking about the Jewish Hasmonaeans who claimed to be God’s chosen rulers. When I was a boy, Israel was actually independent. After the Maccabean revolt threw off foreign rule, many thought that the prophecies of restoration were fulfilled and the wait for Israel’s golden age was over. But eventually the Jewish kings were not much better than foreign ones, and infighting caused them to invite the Romans to come help. The problem is when the Romans help, they help themselves to whatever is best for Rome. When I was a young man just starting on my own, the Romans marched into Jerusalem. We are still waiting for them to leave.

After years of Roman occupation my cousin got tired of waiting. He joined a group of zealots that planned to take Israel’s salvation into their own hands. The Romans heard about the group and crucified them all before they even had a chance to raise their swords in battle. No, only God can bring lasting deliverance. Decade after decade I prayed that God would send the promised Messiah to shine His glory throughout the world and to restore our land. Of course, there were many pretenders who tempted us to think our wait was over – for instance the current king, Herod. He convinced the Romans to install him as our local “Jewish” king (Herod is from Idumea not Israel). Herod craftily pitches himself as a new Solomon. He is re-building the Jerusalem temple so that it is even bigger than Solomon’s. Herod wants people to think he is some sort of savior, but he only uses our faith to get popular support. Herod is just another human pretender – a self-obsessed Roman puppet that will cling to power at all costs. Men like Herod made me long for God to fulfill His promises even more.

All my life I waited for God to send a savior as the prophets foretold. I was not just praying for an end to political pain, but personal pain. I have outlived so many of my family members, even some of my grandchildren. My family and I have suffered from drought, hunger, theft, violence, and death. Countless nights I have prayed Psalm 13, “How long, oh Lord will you forget us forever.” My lament was not because I didn’t believe, but because I knew God as gracious and merciful, slow to anger and abounding in steadfast love. I trusted in the promises He made, so I continually and fervently prayed. Decade after decade I waited faithfully, following what I knew God wanted in my life each day. Faith is not just knowing the prophecies but acting right every day. In my daily life I sought to love my neighbor, to give to those in need, and to point people to God. Every day I tried to live faithfully and expectantly in the waiting. 10 years turned to 20, 20 turned to 30, 30 turned to 40.

Finally, God spoke! The Lord revealed that I would not die until I saw the Lord’s anointed! How did he speak? I didn’t hear an audible voice, but as I read through Isaiah’s prophecies of redemption, the Spirit filled me with a conviction that I would see this Messiah with my own eyes! I had a renewed purpose. I was to be a watchman who waits for this King so that I can announce His arrival! I constantly told people that He was coming soon. I continued praying that I would remain watchful and in God’s will. The Spirit of the Lord was upon me. Yet many more months passed and the Lord’s anointed still didn’t arrive. I experienced more heartaches and more injustice from worldly rulers. I prayed as I had for many years, but with an increased urgency: “Lord, how long? I am getting so old; my body is wearing down. More loved ones have died. How much longer? Nevertheless, I trust you, Lord.” More waiting.

Then last week, the Savior arrived! The Spirit impressed upon me to go to the temple immediately. I went as quickly as these old bones would take me, but I felt a renewed strength as if I was soaring on the wings of eagles (and I certainly was sore the next day). I waited at the gates of the temple, scanning the crowds of worshippers. I prayed that the same Spirit who directed me there would direct me to the right couple.

I noticed a rather plain looking couple carrying an infant. The father had 2 turtledoves- the offering for purification after childbirth that Moses directed in Leviticus. Leviticus actually called for an offering of a lamb and a turtledove. However, the poor could substitute another turtledove for the lamb. The woman looked so young, still in her teens. Just as my eyes were about to move on from this plain, poor couple, I was overwhelmed with the Spirit. This was the one I had been waiting for! I called to the couple, “Wait, let me see your child!” The couple was somewhat startled, but the young woman tilted the infant towards me and said, “This is Jesus. We have come to dedicate him to the Lord our God and give the purification offering.” His name was Jesus, which means “Yahweh saves”! Here was the savior, and the salvation, we had waited for. The prophecy and my purpose were fulfilled. I said to the couple, “Let me bless this child!” I took this child in my arms and said: “Lord, now you are letting your servant depart in peace according to your word; for my eyes have seen your salvation that you have prepared in the presence of all peoples, a light for revelation to the Gentiles, and for glory to your people Israel.”

My mind was overflowing with Isaiah the prophet’s words, which were being fulfilled right in front of me! Almost any scripture from the last third of the scroll seemed relevant to the moment, but one that I have written to keep by my heart is this: “The voice of your watchmen—they lift up their voice; together they sing for joy; for eye to eye they see the return of the Lord to Zion. Break forth together into singing, you waste places of Jerusalem, for the Lord has comforted his people; he has redeemed Jerusalem. The Lord has bared his holy arm before the eyes of all the nations, and all the ends of the earth shall see the salvation of our God” (Isaiah 52:8-10). It was not just the prophetic words of Isaiah that were being fulfilled, but the Lord’s personal word to me that I would not die until I saw the Lord’s Christ.

One day this child will set the captives free, restore sight to the blind, and invite people to repent and enter God’s kingdom! This invitation will not just be to my people; the Messiah will be a light to all nations. Indeed, the Lord God promised our father Abraham that all the nations would be blessed through his descendants. We children of Abraham were not only meant to share in God’s glory ourselves but share it with the nations. Although we have failed at that task many times, the Lord himself is seeing His plan through. This child will bring the light of God to the world and restore the glory of God to Israel. Joy to the world, the Lord has come!

Mary and Joseph marveled, and I pronounced a blessing upon them as well. As I handed the child back to his mother I looked into her eyes (such strong eyes for such a young women) and even more prophetic scriptures flooded my mind. The Lord’s Messiah will bring salvation and restoration, but true restoration requires removing that which is against God. Isaiah spoke of the Messiah as a suffering servant who would take on sin. As this servant takes on that which is against God, he would suffer rejection and even death. This young woman would experience not just the joy of God working through her son, but the sorrow from those who will oppose Him. The prophetic words came out of my mouth before I even realized it: “Behold, this child is appointed for the fall and rising of many in Israel, and for a sign that is opposed (and a sword will pierce through your own soul also), so that thoughts from many hearts may be revealed.”

Just as salvation is centered on this child, this child himself would be the decision point that reveals people’s hearts towards God. God’s purposes will not be universally supported; they will also be opposed. Mary’s son will be the corner stone of God’s kingdom that some builders will reject. My people have a long history of rejecting God’s covenant gifts, and it will be no different in the messianic age. Conflict will arise that will not only expose the hearts of people, it will pierce the heart of this strong, but young mother.

My somber realization was quickly overshadowed by the arrival of Anna, the daughter of Phanuel of the tribe of Asher-a prophetess. Since before Herod even started rebuilding the temple, Anna was a fixture in the temple courts, praying and fasting for the redemption of Jerusalem. When I first met Anna, I asked her about her frequent fasting. She said, “I am a weak widow with no worldly power. Fasting is a type of protest that something is not right. When I fast and pray, I am calling on the power of heaven to come and fix what is not right. I cannot save anyone from the injustice and pain of the world, but God can.” God heard Anna’s pleas, and He often spoke a prophetic word through Anna. Sometimes she would proclaim that God’s redemption was coming and call us to repentance. On that day, the Spirit spoke the same thing to Anna as He spoke to me – your wait is over. Anna joined me in giving thanks to God and witnessing “to all who were looking forward to the redemption of Jerusalem”. Anna and I were the 2 witnesses that God brought together that day to proclaim and celebrate that the wait for the Savior was over!

My somber realization was quickly overshadowed by the arrival of Anna, the daughter of Phanuel of the tribe of Asher-a prophetess. Since before Herod even started rebuilding the temple, Anna was a fixture in the temple courts, praying and fasting for the redemption of Jerusalem. When I first met Anna, I asked her about her frequent fasting. She said, “I am a weak widow with no worldly power. Fasting is a type of protest that something is not right. When I fast and pray, I am calling on the power of heaven to come and fix what is not right. I cannot save anyone from the injustice and pain of the world, but God can.” God heard Anna’s pleas, and He often spoke a prophetic word through Anna. Sometimes she would proclaim that God’s redemption was coming and call us to repentance. On that day, the Spirit spoke the same thing to Anna as He spoke to me – your wait is over. Anna joined me in giving thanks to God and witnessing “to all who were looking forward to the redemption of Jerusalem”. Anna and I were the 2 witnesses that God brought together that day to proclaim and celebrate that the wait for the Savior was over!

I don’t know exactly what will happen as this child grows. I do know he will expose the hearts of many. If Herod finds out, his jealous heart will seek this child’s life. Because of opposition, pain and conflict will continue for a time. While I won’t be around to see exactly what the next step will look like, this child is another reminder that God keeps His promises every step of the way. We can wait on him for the next step. Even if the wait has been long and full of sadness, God does what He says. His plan and purposes are bigger than my short life, even though He called me to be a part of His plan. Now I can depart this world and its troubles in peace, knowing that God’s plan and promises have prevailed and will prevail. Until the day I depart this earth, I will tell this story and invite all to receive this Jesus and God’s salvation. Is your heart open to receive this child? My heart and Anna’s heart are full of joy as we receive this savior, this king – our wait is finally over! With my last breath, this watchman can call out, “Joy to the world the Lord has come, let earth receive her king!”

The Book of Revelation’s Structure

In the midst of an earthquake and eclipse in the Northeast United States, I was preparing to teach the book of Revelation for a New Testament Survey course. My preparations put these unusual phenomenon in their proper perspective. For one, John’s Apocalypse describes world-wide, end of time, events. Despite what residents of the Northeast U.S. might think, we are not the center of the world or history – especially salvation history. Most Christians today live in the global South and Revelation doesn’t even mention the United States. Second, the book of Revelation is cyclical, so the signs of the end-times will be things that have happened before and will follow patterns of intensification. The tribulations, disasters, and signs that it describes are drawn from Old Testament imagery. Revelation looks forward AND backwards to encourage people in the present to persevere in their faith. We often get lost in the strange details of Revelation and miss out on the stabilizing sovereignty of God featured in the book’s storyline. For this reason, an overall structural outline of Revelation is both needed and helpful.

In my opinion, Craig Koester has developed one of the best graphic outlines of Revelation’s cyclical structure (Revelation and the End of All Things, Eerdmans, 2018, pg 42–43). Scholars can’t seem to agree on an outline that accounts for all of Revelation’s quirks, twists, and turns, but Koester’s graphic accounts for several features of Revelation. Koester explains, “An outline of the book looks like a spiral, with each loop consisting of a series of visions: seven messages to the churches (Rev. 1–3), seven seals (Rev. 4–7), seven trumpets (Rev. 8–11), unnumbered visions (Rev. 12–15), seven plagues (Rev. 15–19), and more unnumbered visions (Rev. 19–22). Visions celebrating the triumph of God occur at the end of each cycle (4:1–11; 7:1–17; 11:15–19; 15:1–4; 19:1–10; 21:1–22:5). Those who read Revelation as a whole encounter visions that alternately threaten and assure them. With increasing intensity the visions at the bottom of the spiral threaten the readers’ sense of security by confronting them with horsemen that represent conquest, violence, hardship, and death; by portents in heaven, earth, and sea; and by seemingly insuperable adversaries who oppose those who worship God and Christ. Nevertheless, each time the clamor of conflict becomes unbearable, readers are transported into the presence of God, the Lamb, and the heavenly chorus. These visions appear at the top of the spiral. Threatening visions and assuring visions function differently, but they serve the same end, which is that readers might continue to trust in God and remain faithful to God.”

I have interwoven Koester’s explanation onto his spiral graphic to show how it works as a general outline. Too often in Revelation, we “can’t see the forest for the trees.” All of the strange details and symbols draw our focus away from the big picture. Therefore, keeping a big picture (or graph in this case) in view can help us follow the main themes and story line. Most of Revelation’s content, themes, and literary structure fit into this outline (although no outline is perfect). Many scholars note Revelation’s visions have patterns of sevens (a number that symbolizes universality or completion) that overlap and repeat earlier material while still advancing towards a finale. Each cycle spirals down into tribulation on the earth followed by a glimpse into heaven to show the sovereign God/Christ moving events towards victory. This patterned presentation, when coupled with frequent Old Testament allusions and symbols, doesn’t just look forward; it looks back to the history of God’s people oppressed and tempted by evil powers. Babylon pursued and persecuted the Israelites of old, and a new Babylon (Rome in John’s day) seeks to destroy and tempt God’s people. The sovereign Lord reigns over all of history; this includes the history of the suffering saints addressed in Revelation’s first three chapters. Yes, there will be eclipses, earthquakes, diseases, and war. God’s people will be persecuted. These patterns were present in Israel’s day, in John’s day, and in our day. However, all these patterns will one day culminate in the final judgment and redemption when Christ returns. Believers don’t know when that day will be; but it is sooner than it was when Revelation was written. The sovereign God of the universe, and the Lamb who was slain for our redemption, directs history. Even when the world is in great upheaval, God’s people have a secure place in Christ. For this reason, Revelation’s call to persevere in the faith is timeless and bigger than the events of our day. At the end of Revelation, Jesus reminds us: “Behold, I am coming soon. Blessed is the one who keeps the words of the prophecy of this book.” (Rev 22:7).

An updated table arranging the New Testament books according to the date of composition.

This blog’s all-time most read post (found here ) contains a table arranging the New Testament (NT) books according to the date they were written. As I have been preparing a NT survey course, I felt the need to slightly update the chart. One such update concerns the Epistle of James. In my first chart, I underestimated the number of conservative scholars who consider James to be the first NT book written. For instance, Carson & Moo’s Introduction to the NT, Dan McCartney’s BECNT commentary, as well as Blomberg & Kamell’s ZECNT commentary suggest that James was written in the mid to late 40s.

The other changes are adjustments to the dates (and therefore their order in the table) that reflect a broader survey in my own reading. Below, I also reproduce the introduction to my original 2018 post.

_______________________________________________________________

Our modern New Testaments are not arranged chronologically, which sometimes causes misunderstandings. While the Gospels discuss the events of Jesus’ life (the crucifixion took place in 30 or 33 A.D.), the earliest Gospel probably was written down about 60. The Apostle Paul wrote many of his letters before the Gospels. This historical perspective is helpful when assessing arguments over material that some scholars may deem a “later theological development” in the early church. For example the “kenotic hymn” of Philippians 2 exhibits a very high view of Christ, despite Paul most likely writing Philippians before the Gospel writers completed their writings. Note the exalted status afforded to Christ:

Have this attitude in yourselves which was also in Christ Jesus, who, although He existed in the form of God, did not regard equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied Himself, taking the form of a bond-servant, and being made in the likeness of men. Being found in appearance as a man, He humbled Himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross.

Philippians 2:5-8 (NAU)

Some scholars believe these verses were a pre-existing hymn that Paul incorporated into his letter. If this theory is correct, then the high view of Christ can be traced to an even earlier time. Arguments, therefore, that assume a high view of Christ (i.e. his divinity) always reflects a later church development contain an invalid presupposition.

The table below arranges the NT books by their likely date of composition. Most NT books are difficult to date with precision, which is why discussions about dating can often be lengthy and still not definitive. The dating of the various writings depends on views of authorship, so I have included two columns of dates. The books are listed chronologically, according to their more conservative dating, but the right hand column provides dates from a more skeptical view. Of course, these dates are further debated within their respective “conservative” and “skeptical” camps, but I have tried to give the most common views from my own subjective survey of the data. For the most part, I have disregarded the “outliers” of either camp. I hope readers find the following table helpful.

| Earlier, more conservative dating | NT Book (Listed by date of Composition) | Later, more skeptical dating |

| 45-60 | James | 70-100 |

| 48-Late 50s | Galatians | 50s |

| Early 50s | 1 Thessalonians | Early 50s |

| Early 50s | 2 Thessalonians | Early 50s (later if forged) |

| Mid 50s | 1 Corinthians | Mid 50s |

| Mid 50s | 2 Corinthians | Mid 50s |

| Approximately 57 | Romans | Approximately 57 |

| Early 60s | Philemon | 60s |

| Early 60s | Philippians | 60s |

| Early 60s | Colossians | Early 60s (70-90 if forged) |

| Early 60s | Ephesians | 70-90 |

| Early 60s | 1 Timothy | 90-110 |

| Early 60s | 1 Peter | 70-100 |

| 60s | Gospel of Mark | Late 60s-70s |

| Mid 60s | Titus | 90-110 |

| Mid 60s | 2 Timothy | 90-110 |

| Mid 60s | 2 Peter | 90-110 |

| Late 60s | Hebrews | 60-95 |

| Late 60s | Gospel of Matthew | 80-100 |

| Late 60s-80 | Gospel of Luke | 80-100 |

| Late 60s-80s | Acts | 85-130 |

| 60-80 | Jude | 80-110 |

| 80-90 | Gospel of John | Approximately 100 |

| Early 90s | 1 John | 100-125 |

| Early 90s | 2 John | 100-125 |

| Early 90s | 3 John | 100-125 |

| Late 60s or mid 90s | Revelation | 100-125 |

The Book of Acts: God-directed Mission

The next few posts will introduce some major themes in the “Acts of the Apostles”. This title appears in several ancient manuscripts of the New Testament, but as Darrell Bock (2007, 7) suggests, the main character of Acts is not the apostles as much as the Triune God, who “enables, directs, protects, and orchestrates. Nothing shows this as much as the story of Paul, who comes to faith by Jesus’ direct intervention and is protected as he travels to Rome, despite shipwreck.” The Spirit empowers the apostles and early church to be witnesses for Christ’s salvation from Jerusalem to the “ends of the earth” (Acts 1:8). The extension of God’s kingdom throughout the earth fulfills God’s long standing promises to “pour out his Spirit on all flesh” (Acts 2:17; Joel 2:28-32) and to call the Gentiles to himself (Acts 13:47; Isa 49:6. Acts 15:14-18; Amos 9:11). The “way” of Christ is not a new religion, but a continuation of God’s promised plan to redeem the world. Spirit inspired testimony to Christ goes throughout the known world – from servants to governors, from Jews to Samaritans to even the Gentiles in Rome.

God uses persecution to advance the Gospel.

Even persecution can be used by the sovereign God to advance the gospel. The early chapters of Acts report the tremendous growth of the church in and around Jerusalem. Initially, Jesus’ commission for the apostles to spread the gospel to the ends of the earth (Acts 1:8) goes unfulfilled. God sovereignly used the Jewish leaders’ hostility towards the church to spread the Christian witness to new areas. By killing and persecuting Christians, the Jewish leaders hoped to crush the Christian movement. But what they meant for harm, God used to spread the gospel.

The stoning of Stephen began the first widespread persecution, which caused Christians to flee Jerusalem and “scatter throughout the regions of Judea and Samaria” (Acts 8:1). Ironically, this persecution was led by a zealous young Jew named Saul, who would later spread the Christian movement even farther. Lenski (1961, 311-315) notes, “The persecution aimed to destroy the infant church; in the providence of God it did the very opposite. It started a great number of new congregations especially in all of Palestine, each becoming a living center from which the gospel radiated into new territory even as Jesus had traced its course by adding after Jerusalem ‘all Judea and Samaria’ . . . These were ordinary Christians; they did not set themselves up as preachers but told people why they had to leave Jerusalem and thus testified to their faith in Christ Jesus. They fulfilled the duty that is to this day incumbent on every Christian. In 11:19 Luke indicates how far this dispersion reached: to Phoenicia, Cyprus, and Antioch.”

Jesus’ commission to witness to “Judea, Samaria, and the ends of the earth” was now being fulfilled. As if to show that God was fully in control, even the one who led the persecution—Saul, ends up becoming an apostle to the Gentiles. By the end of the book of Acts, Saul the persecutor has become Paul the persecuted. Saul led a persecution that spread Christianity to Judea and Samaria, and now Paul was himself being persecuted so that he would bring the gospel to Rome and the ends of the earth. God’s utilizing even persecution to further his purposes provides another reason for seeing the Triune God as the main actor in the book of Acts.

End Notes

Bock, Darrell. Acts. BECNT; Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2007.

Lenski, R. The Interpretation of the Acts of the Apostles. Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1961.

Parsons, M. Acts. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008.

Miracles in the Four Gospels : A Discussion and helpful reference table.

Jesus’ teaching (often through parables) and miracles are primary features of the Gospels. A biblically informed definition of a miracle would consider a miracle as “an event which runs counter to the observed processes of nature” (EDT, 779). Certainly prophecy or special knowledge could fit into this definition, but most treat those phenomena in their own category.

Miracles in the Bible are evidence of God’s direct intervention in the world. Just as miracles are displays of God’s power in the space and time of this world, faith in the God who works those miracles calls for a lived-out response in a believer’s life. Neither biblical faith nor biblical miracles are just “religious” concepts or theories of the mind; they are observable holy disruptions in a fallen word on its way to redemption. For this reason, when God intervenes to redeem people of faith, his power and presence produce miracles. The miracles surrounding the exodus from Egypt exemplify this pattern. While the plagues and parting of the sea were incredible displays of God’s power, they were performed in the context of God fulfilling his redemptive promises to his people.

In keeping with the OT pattern, the arrival of God’s Kingdom in the person and work of Christ was predictably accompanied by miracles. Jesus’ miracles proclaimed in actions the same message proclaimed in his words: “The Kingdom of God is at hand.” Moreover, the miracles demonstrated Jesus’ identity as the promised Messiah who would usher in this new age of redemption. The resurrection of Jesus was the pinnacle of all miracles and the firstfruits of the new age of redemption and resurrection.

In the NT Jesus is not the only person to work miracles. Every Gospel contains a passage about Jesus giving his followers authority and power to perform miracles (Matt 6:7, 12-13; Mark10:1; Luke 9:1-2, 6; John 14:12). Not surprisingly, the apostles perform miracles in the book of Acts (3:1-11; 5:12-16; 19:11-12), and Paul mentions miracles taking place in the early churches apart from an apostle’s presence (1 Cor 12:6-10, 28-31; Gal 3:5; ).

Why do the Gospel writers incorporate miracles into their writings? While each writer employs miracles for their own distinct purposes, some general observations can be made. 1) Because Jesus actually performed miracles, any biography about him would include this remarkable aspect of his life. 2) As mentioned above, miracles accompany turning points in God’s redemptive plan: “Thus the Synoptists regarded Jesus’ miracles. . . as one mode of God’s assertion of his royal power, so that while the kingdom in its fullness still lies in the future, it has already become a reality in Jesus; words and works” (DJG, 550). This idea is captured in Jesus’ dispute with the Pharisees over the source of Jesus’ power. Jesus says, “But if it is by the finger of God that I cast out demons, then the kingdom of God has come upon you.” (Luke 11:20; Matt 12:28). God’s kingdom brings God’s power to do miracles. 3) Just as the miracles identify the advent of God’s kingdom, the miracles identify Jesus as the anointed Messianic king. As demons are cast out, they proclaim Jesus’ identity as the Holy One (or Son) of God (Mark 1:21-27; Luke 4:31-36; Matt 8:28-34). When Jesus walks on water, the disciples worship him and say, “Truly you are the Son of God” (Matt 14:33). In a similar way, the miraculous signs of John’s Gospel point to Jesus’ glorious identity (John 2:11; 5:36). 4) Because miracles identify Jesus as the Messiah, it is no surprise that miracles are closely associated with faith in Jesus. In John, miraculous signs are usually meant to bring about faith, but in the Synoptics faith often precedes miracles (Matt13:58; Mark 5:34; Luke 17:19). What exactly is meant by faith/belief varies according to the author and the context. The blind man in John 9 believes that Jesus is the Son of Man and worships him (John 9:35-38), whereas the father in Mark 9:21-27 struggles with believing that Jesus is able to heal his son. At the very least, the Gospels present miracles as both confirming and encouraging faith in Jesus.

Table of Miracles

In the table below miraculous healings are in regular font, exorcisms employ italic font, and miracles over nature/materials are underlined. These different fonts are not meant to suggest that the Gospel writers thought in these different categories (especially concerning healings and exorcisms), but to show how the Gospel writers employed these miracles. Although the resurrection of Christ should be considered the pinnacle of all miracles, it is not included in this chart because it deserves its own separate treatment. Likewise, the appearance of angels around the birth narratives could be considered miraculous, but like appearances of the risen Jesus, they are not included below.

| Miracles in the Gospels | ||||

| Description | Matthew | Mark | Luke | John |

| Turning water into wine at Cana | 2:1-11 *sign | |||

| General statement of healing all types of sicknesses in Galilee | 4:23-24 | 1:39 “preaching and casting out demons” | ||

| Cana: Healing son (not present) of royal official | 4:46-54 *sign | |||

| Exorcism in Capernaum (Confess Jesus as Holy one of God) | 1:21-27 | 4:31-36 | ||

| Healing Peter’s Mother-in-law and many others | 8:14-17 | 1:29-34 | 4:38-41 | |

| Removal/cleansing of leprosy-then more fame * | 8:2-4 | 1:40-45 | 5:12-15 | |

| Healing the servant of a Centurion with great faith | 8:5-13 (servant not present) | 7:1-10 (servant & centurion not present) | ||

| Miraculous catch of fish | 5:1-11 | |||

| Paralytic healed & forgiven | 9:1-8 | 2:1-12 (lowered through roof.) | 5:17-26 (lowered through roof.) | |

| Healing invalid at Bethesda on Sabbath | 5:1-17 *sign | |||

| Heals withered hand on Sabbath * | 12:9-14 | 3:1-6 | 6:6-11 | |

| General statement: exorcised spirits confess Jesus as Son of God. | 3:10-12 | |||

| Raising a dead man at Nain | 7:11-17 | |||

| The women who followed Jesus were cured of sickness or demons | 8:1-3 | |||

| Calming the storm on the sea of Galilee | 8:23-27 | 4:37-41 | 8:22-25 | |

| Legion of demons cast into swine. | 8:28-34 (Confess Jesus as Son of Most High God) | 5:1-20 (Confess Jesus as Son of Most High God) | 8:26-39 (Confess Jesus as Son of God) | |

| Raising synagogue ruler’s dead daughter and healing a woman’s blood flow on the way | 9:18-26 | 5:21-43 | 8:40-56 | |

| 2 blind men healed | 9:27-31 | |||

| Disciples given authority to heal and cast out demons | 10:1 | 6:7, 12-13 | 9:1-2, 6 | |

| Casting out demon from mute man – Pharisees blaspheme | 9:32-34 12:22-24 | 11:14-15 | ||

| Feeding five thousand | 14:15-21 | 6:35-44 | 9:12-17 | 6:5-13 *sign |

| Jesus Walks on Water | 14:25-33 (Peter joins him) | 6:48-52 | 6:19-21 | |

| General statements of curing many | 9:35 14:34-36; 15:29-31 | 6:53-56 | 6:17-19 | 6:2; 20:30 |

| Healing man born blind on Sabbath, interrogated by Jewish leaders | Ch 9 *sign | |||

| Casting demon from daughter (not present) of Gentile | 15:21-28 | 7:24-30 | ||

| Healing of deaf man with speech difficulty | 7:31-37 | |||

| Feeding the four thousand | 15:32-38 | 8:1-9 | ||

| Healing blind man at Bethsaida | 8:22-26 | |||

| Casting demon out of son who convulses | 17:14-20 | 9:14-29 | 9:37-43 | |

| Temple tax in fish’s mouth | 17:24-27 | |||

| Healing a sick by spirit & hunched over woman on Sabbath | 13:10-17 | |||

| Healing man of dropsy on Sabbath | 14:1-6 | |||

| Raising Lazarus | 11:1-45 *sign | |||

| 10 lepers healed; Samaritan returns to thank | 17:11-19 | |||

| Blind healed at Jericho | 20:29-34 (2 blind men) | 10:46-52 (Bartimaeus) | 18:35-43 (unnamed) | |

| Healing many in Temple courts | 21:14 | |||

| Fig tree withered | 21:18-22 | 11:12-14, 20-25 | ||

| Healing the servant’s ear after Peter cut it off | 22:50-51 | |||

| Miraculous catch | 21:1-11 |

The above table reveals some patterns. 1) All the Gospels contain general statements about Jesus performing other miracles. One should assume, therefore, that the Gospel writers only chose a select few miracles in their presentation of Jesus. 2) Each Gospel describes at least one miracle that is not mentioned in the other Gospels. 3) Assuming Mark was written first, one notices that when Matthew and Luke contain Mark’s miracles, they seem to follow Mark’s ordering of the miracles. The two occasions (marked with a *) that Matthew or Luke have a different ordering of the same miracle, they never agree against Mark. Instead Mark and one of the other Gospels match sequences. 4) John contains by far the fewest miracles. Of the eight miracles listed, only two appear in the other Gospels—Jesus’ feeding the five thousand and walking on water. That being said, all the other miracles (other than the water made into wine) in John are similar in type to the miracles described in the Synoptic (healings, walking on water, miraculous catch of fish).

An overview of the miracles also gives insight into the distinctive presentation of each Gospel writer. For instance, in the Gospel of Mark “(t)he virtual absence of miracle stories after Jesus arrives in Jerusalem allows full rein to the hints of the theme of Jesus’ self-giving expressed in the earlier miracle stories. Jesus the powerful miracle worker chooses to offer himself, powerless, into the hands of the authorities in order to die ‘for many’ (10:45). . . . Some of Jesus’ commands to his disciples to remain silent indicate that his true identity cannot be fully understood apart from his passion and death (1:11, 34; 3:12); the powerful miracle worker without the suffering Jesus is an incomplete and misunderstood Messiah.” (NDBT, 777)

Luke presents Jesus’ ministry of preaching and healing as a product of his Spirit anointing (Luke 4:14-21). In fulfillment of Isaiah, the Spirit anoints and empowers Jesus to bring a restoration that includes healing the blind and release those held captive by all manner of oppression (including sickness). Jesus’ working of miracles is evidence that he has been empowered by God to advance his kingdom (Luke 11:20). When Luke writes Acts, he states that this same Spirit will empower Jesus’ followers to expand Christ’s kingdom (Acts 1:8). After Pentecost, miracles accompany the apostles as they proclaim the gospel of Christ’s kingdom.

How particular miracles function in each Gospel will be discussed more fully later. Taking a broad view of miracles shows that they are a prevalent feature of Jesus’ ministry. The Gospel writers weave miracles into their presentations to say something about Jesus’ identity, his kingdom, and the faith of those Jesus encounters.

END NOTES

*DJG: Green, Joel and Scot McKnight, eds. Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels. Downers

Grove: InterVarsity, 1992.

*EDT: Elwell, Walter, ed. Evangelical Dictionary of Theology. 2nd ed. Grand Rapids:

Baker, 2001.

* NDBT: Alexander, T. Desmond, et. al. New Dictionary of Biblical Theology. Downers

Grove: InterVarsity, 2000.

An Introduction to Parables and their Interpretation.

Parables make up about one third of Jesus’ teaching in the Synoptic Gospels. In order to properly understand the Synoptic Gospels, therefore, one must be familiar with the definition, function, and forms of parables.

Because parables vary in their form and usage, it is difficult to construct an accurate but usable definition. Blomberg (1997, 257) gives the very basic definition: “A parable is a brief metaphorical narrative.” This definition covers the broad usage of parables, but it is so general that further description is needed. A parable consists of a fictional picture or story and a corresponding reality that is better understood through that picture or story. For instance, in Matt 13:31-32 Jesus tells the following parable: “The kingdom of heaven is like a grain of mustard seed that a man took and sowed in his field. It is the smallest of all seeds, but when it has grown it is larger than all the garden plants and becomes a tree, so that the birds of the air come and make nests in its branches.” The picture or story element is the man who plants a tiny mustard seed that grows into a tree large enough for nesting birds. The reality element, which is better understood through this story, is the kingdom of heaven. Often one has to examine the context of the parable to narrow down what particular meaning the correspondence conveys. In this parable, the smallness of the mustard seed corresponds to the relatively small effect the Kingdom of Heaven seems to have in the present age. However, the kingdom will eventually grow bigger and more influential than anything else in the world (field). Through the picture, Jesus’ hearers gain a deeper understanding of how the Kingdom of Heaven manifests itself.

While parables occur in the broader ancient Hebrew and Greek literature, Jesus seems to have used parables to a greater extent than any of his predecessors. Parables rarely appear in the Old Testament (OT), but Nathan’s rebuke of King David (2 Sam 12:1-10) is the OT parable most similar to Jesus’ parables. Other OT parables are found in: 2 Sam 14:5-20; Isa 5:1-7; Ezek 17:1-10; 19:1-9, 10-14.

While parables occur in the broader ancient Hebrew and Greek literature, Jesus seems to have used parables to a greater extent than any of his predecessors. Parables rarely appear in the Old Testament (OT), but Nathan’s rebuke of King David (2 Sam 12:1-10) is the OT parable most similar to Jesus’ parables. Other OT parables are found in: 2 Sam 14:5-20; Isa 5:1-7; Ezek 17:1-10; 19:1-9, 10-14.

Parables prominently feature in the Synoptics, but not in any other New Testament (NT) book (other than two uses of the word “parable” in Heb 9:9; 11:9). Some consider the “Good Shepherd” and “True Vine” passages (John 10:1-18; 15:1-8) as parables, but John seems to employ these as “I am” sayings and not as parables. Regardless, John presents Jesus’ teaching very differently than the Synoptics by not explicitly including parables.

Some parables occur in all three Synoptics, while others appear in only one. The Gospel writers arrange parables in different ways, often grouping them thematically. Sometimes it is difficult to discern if the Gospel writers are reporting the same parable (Matt 25:14-30 & Luke 19:11-27). Perhaps Jesus told variations of a given parable in different places, and the Gospel writers were reflecting those different renditions. Below is a table of parables in the Synoptics, but the reader should understand that such catalogues of parables differ slightly because scholars differ on the exact qualifications of a parable.

| Parable Title | Matthew | Mark | Luke |

| Parables of the groom, cloth, wineskins | Matt 9:14-17 | Mark 2:18-22 | Luke 5:33-39 |

| Blind leading the blind; pupil leading teacher | (Matt 15:14) | Luke 6:39-40 | |

| 2 houses built on 2 different types of ground | Matt 7:24-27 | Luke 6:46-49 | |

| A forgiving money lender | Luke 7:40-50 | ||

| House divided; binding the strong man | Matt 12:24-29 | Mark 3:22-27 | (Luke 11:15-22) Not binding a strong man, but being stronger. |

| Parable of the sower/soils receiving seed/word of God | Matt 13:1-23 | Mark 4:1-20 | Luke 8:4-15 |

| A lamp is not hidden | Matt 5:15 | Mark 4:21-23 | Luke 8:16-18; 11:33 |

| The children and the marketplace | Matt 11:16–19 | Luke 7:31–35 | |

| Kingdom is like: weeds sown in a field | Matt 13:24-30, 36-43 | ||

| Kingdom is like: seeds’ sudden growth | Mark 4:26-29 | ||

| A friend at midnight | Luke 11:5-8 | ||

| Kingdom is like: mustard seed | Matt 13:31-32 | Mark 4:30-32 | Luke 13:18-19 |

| Kingdom is like: leaven | Matt 13:33-35 | Luke 13:20-21 | |

| Kingdom is like: hidden treasure | Matt 13:44 | ||

| Kingdom is like: merchant finding a valuable pearl | Matt 13:45-46 | ||

| Kingdom is like: a dragnet | Matt 13:47-50 | ||

| Disciple as head of household | Matt 13:52 | ||

| Defiled by what comes out, not what enters | Matt 15:10-20 | Mark 7:14-23 | |

| Kingdom is like: a king forgiving a slave, but that slave not forgiving | Matt 18:23-35 | ||

| Good Samaritan-loving neighbor | Luke 10:30-37 | ||

| Folly of building storehouses | Luke 12:13-21 | ||

| Giving the Fig tree another chance | Luke 13:6-9 | ||

| Guests taking the more humble seat | Luke 14:7-11 | ||

| The tower builder and the warring king | Luke 14:28-33 | ||

| The lost sheep, the lost coin, and the lost son. | Matt 18:12-14; (just lost sheep) | Luke 15 | |

| The shrewd manager | Luke 16:1-13 | ||

| The rich man and Lazarus | Luke 16:19-31 | ||

| A slave just doing what he is supposed to | Luke 17:7-10 | ||

| The unrighteous judge and the persistent window. | Luke 18:1-8 | ||

| The praying Pharisee and humble tax-collector. | Luke 18:9-14 | ||

| Kingdom is like: a landowner hiring workers for vineyard | Matt 20:1-16 | ||

| Two sons in a vineyard | Matt 21:28-32 | ||

| Wicked Vine growers | Matt 21:33-45 | Mark 12:1-12 | Luke 20:9-19 |

| Kingdom is like: a wedding feast | Matt 22:1-14 | Luke 14:16-24(same parable?) | |

| Fig Tree predicts summer | Matt 24:32-33 | Mark 13:28-29 | Luke 21:29-31 |

| Servants alert for their master’s return | Matt 24:45f? | Mark 13:33-37 | Luke 12:35-48?? |

| Kingdom is like: 10 virgins waiting for the groom. | Matt 25:1-13 | ||

| A master goes away and tasks servants to use his money until he returns | Matt 25:14-30 | Luke 19:11-27 (same parable?) |

The two most prevalent themes in the parables are the Kingdom of God (the nature of its coming) and citizenship in that kingdom (discipleship). K. Snodgrass (DJG, 599-600) categorizes parables according to what kingdom reality they describe: 1) The kingdom as present. Some parables answer questions concerning how God’s kingdom is present in Jesus’ work and ministry. The parable of the strong man (Matt 12:25-28) means Jesus is plundering Satan’s current domain on earth, and the parable of the leaven (Luke 13:20-21) explains how the kingdom seems to be small at the present time.

2) Kingdom as future. Other parables focus on aspects of the kingdom that are still future. The parables that picture a reckoning or judgment (Matt 22:1-14; 25:14-30) fall into this category, as they encourage faithfulness in preparation for a final day of judgment.

3) Discipleship. Other parables explain what following the heavenly King entails. Being a citizen of Christ’s kingdom requires counting the cost like a warring king (Luke 14:28-32), being like a shrewd manager in the use of earthy wealth for heavenly purposes (Luke l6:1-13), and praying with a humble, tax-collector-like, spirit (Luke 18:9-14).

Guidelines for Interpreting Parables.

Guidelines for Interpreting Parables.

The interpretation of parables has had a tangled history. Within a couple centuries of being written down by the Gospel writers, parables began to be interpreted allegorically by the church fathers. Saint Augustine famously attached allegorical meaning to every detail of the parable of the Good Samaritan. The Samaritan represented Christ, the robbers represented the devil, the inn represented the church (which didn’t even exist at the time Jesus spoke the parable), the beaten man represented Adam, and so on. While not all church fathers interpreted the parables allegorically, it was the dominant interpretive method of their day, and it continued to be until after the reformation. In the 1900s the allegorical interpretation was discredited and almost entirely thrown out. It was replaced with an assumption that parables originally contained no allegory and were simple comparisons with only one main point. In contemporary scholarship more balanced literary views have developed that acknowledge that parables may not be allegories, but they can contain allegorical elements. What, then, are some guidelines in interpreting parables?

A. Because parables contain a story/picture part and a reality part, first identify the familiar picture element(s) and the reality or truth being explained. For example in the parable of the forgiving money lender in Luke 7:40-50 the picture/story element is the money lender who forgave one debtor 50 denarii and another debtor 500 denarii. The reality or truth part being explained concerns the relationship between forgiveness and love. While much more needs to be understood about the parable, it is essential to first clarify what part is the story/picture and what is the truth/reality being explained.

B. Remember the fictional story/picture part of the parable should be interpreted as a fictional composition. As Robert Stein (1994, 137-8) explains, “The picture itself does not describe an actual historical event. It is a fictional creation that came into being out of the mind of its author. . . . We must not confuse a life-like parable, which is a fictional creation, with a biblical narrative referring to a historical event.” The questions we should ask of a parable, therefore, are not about the details of the story, but what spiritual truth the author is trying to highlight with this story. In the example of the forgiving money lender, we should not be asking how the debtors incurred their debt—the creator of the parable did not include that information because it did not help make his point. Usually the details of the story don’t have their own meaning; they simply fill out and support the main picture. The author didn’t intend every detail of the parable to carry its own allegorical meaning totally unknown to the original audience.

C. Search the context for any explanation or interpretation provided by the author. In the above parable of the forgiving money lender, the parable is embedded in a narrative that contains dialogue. Both the narrative and the dialogue point to the spiritual reality that the parable explains. After telling the parable, Jesus compares the Pharisee’s lack of hospitality to the sinful woman’s lavish and loving treatment of Jesus. Jesus then proclaims, “Therefore, I tell you, her many sins have been forgiven—for she loved much. But he who has been forgiven little loves little” (Luke 7:47). This material after the parable (the context) repeats and applies the spiritual truth that a person’s reception of Jesus (love) flows from the forgiveness received. It is in the context that the spiritual truth/reality part of the parable becomes clear. Some parables’ contexts are not quite so helpful, but context usually gives important clues to the author’s intention.

In addition to the above guidelines, the Lexham Bible Dictionary provides the following six basic principles for understanding Jesus’ parables.

1. Understand the social, historical, and cultural context of the parable. For example, in the parable of the Persistent Widow (Luke 18:1–8), it helps to know that in the first-century widows often experienced significant hardship and oppression.

2. Determine the number of points the parable is intended to teach. This may be linked to the number of main characters in the parable (Blomberg, Interpreting the Parables, 174).

3. Consider to whom the parable is directed. Is the audience being addressed the disciples, the Jewish leaders, or the crowds? The identity of the audience will help indicate the message that the parable was intended to communicate.

4. Realize that repetition in parables is for the purpose of stressing a major point.

5. Identify stock symbolism being employed. For example, God is commonly pictured throughout the Bible (and in parables) as a father, king, judge, shepherd, etc.

6. Note the conclusion of the parable. The last person, deed, or saying often conveys the significance of the parable.

By applying the above guidelines, one should be able to identify the author’s main point(s), which are closely attached to the spiritual reality the parable pictures.

The Parable of the Sower as a Challenge to the Purpose and Interpretation of Parables.

The parable of the sower (Matt 13:1-23; Mark 4:1-20; Luke 8:4-15) challenges many of the concepts presented above. For one, it suggests that parables were meant to obscure understanding and not increase it. Secondly, Jesus assigns meaning to several of the elements of the parable (like an allegory). It is helpful, therefore, to examine more closely this parable about parables.

With some variation in details, the parable of the soils appears in all three Synoptic Gospels. The main points and context of the parable are mostly consistent in each of the Gospel’s retelling, but for expediency we will examine only Matthew’s version (13:1-23). Jesus tells the parable to a large crowd (13:2). Verses 3-9 describe Jesus’ words to the crowd: “Then he told them many things in parables, saying, ‘A farmer went out to sow his seed. As he was scattering the seed, some fell along the path, and the birds came and ate it up. Some fell on rocky places, where it did not have much soil. It sprang up quickly, because the soil was shallow. But when the sun came up, the plants were scorched, and they withered because they had no root. Other seed fell among thorns, which grew up and choked the plants. Still other seed fell on good soil, where it produced a crop– a hundred, sixty or thirty times what was sown. He who has ears, let him hear.’” Using the guidelines above, we first attempt to identify the story part and the reality part of the parable. Up to this point we seem to have the story part, the sowing of seed on various types of soil to various results, but the reality part is unclear. There is no introduction like “the Kingdom of Heaven is like.” Similar to Jesus’ original audience, we are not certain what spiritual reality this story is supposed to help us understand. From Jesus’ religious background, a few clues can be found; seed for sowing was associated with God’s word (Isa 55:10-11; John 4:36-38; 1 Cor 3:6-8) and bearing fruit was a metaphor for godly prosperity (Psa 92:12-14; Isa 5:2; Ezek 17:5-10; John 15:1-8; Rom 7:4). Even with these connections, the main point of the parable remains unclear. We look to the context hoping to find explanation.

In this case, the context does not disappoint; it contains Jesus’ full explanation and interpretation of the parable. Jesus later explains the meaning of the parable privately to the disciples: “Listen then to what the parable of the sower means: When anyone hears the message about the kingdom and does not understand it, the evil one comes and snatches away what was sown in his heart. This is the seed sown along the path. The one who received the seed that fell on rocky places is the man who hears the word and at once receives it with joy. But since he has no root, he lasts only a short time. When trouble or persecution comes because of the word, he quickly falls away. The one who received the seed that fell among the thorns is the man who hears the word, but the worries of this life and the deceitfulness of wealth choke it, making it unfruitful. But the one who received the seed that fell on good soil is the man who hears the word and understands it. He produces a crop, yielding a hundred, sixty or thirty times what was sown.” (Matt 13:18-23) Seldom are the parables given such a clear and thorough explanation. The story of the sower helps the listeners understand the spiritual reality of the word of God producing varied results among those who hear it.

Jesus’ detailed interpretation raises questions about interpreting parables. The guidelines above state that details of parable should not be given individual allegorical interpretations, but Jesus seems to do just that in his interpretation. Each place the seed lands is given an allegorical meaning that corresponds to different people’s reception of “the message about the kingdom.” This parable shows that although most parables are not simply allegories, they can have allegorical elements. While allegorical interpretation of parables is to be avoided, one must still acknowledge that parables may contain allegorical elements. The meaning of these elements should come from the author or from common metaphors of the author’s culture—not from the interpreter’s imagination or context (as was often the case in the medieval church).

In between Jesus’ telling and explanation of the parable, the Gospel writers introduce another element to this parable. While this parable helps listeners understand the spiritual reality of the word of God producing varied results among those who hear it, the parable also says something about how parables themselves produce varied results among hearers. After Jesus tells the parable, the disciples ask why Jesus teaches in parables, implying that this parable is unclear. Jesus’ reply suggests that parables are meant to obscure understanding instead of increase it—a concept that seems counterintuitive. After all, most parables use familiar elements to paint a picture comparison of an unfamiliar spiritual truth. In response to the disciples question about the purpose of parables, Jesus answers, “The knowledge of the secrets of the kingdom of heaven has been given to you, but not to them. Whoever has will be given more, and he will have an abundance. Whoever does not have, even what he has will be taken from him. This is why I speak to them in parables: ‘Though seeing, they do not see; though hearing, they do not hear or understand.’ In them is fulfilled the prophecy of Isaiah: ‘You will be ever hearing but never understanding; you will be ever seeing but never perceiving. For this people’s heart has become calloused; they hardly hear with their ears, and they have closed their eyes. Otherwise they might see with their eyes, hear with their ears, understand with their hearts and turn, and I would heal them.’ But blessed are your eyes because they see, and your ears because they hear.” (Matt 13:11-16). Jesus explains that the disciples are blessed by having a fuller knowledge of the Kingdom of Heaven than others. This knowledge relates to what they already have—a close relationship with Jesus. By virtue of this relationship, the disciples will receive Jesus’ full interpretation of the parable; they truly see and hear. Truly hearing corresponds to the good soil of the parable, which is why the disciples are blessed; they will produce much fruit.

On the other hand, many will not receive this parable or any message about the Kingdom of Heaven. These people are not only like the soils that aren’t productive, they are like those spoken of by the prophet Isaiah: “ever hearing but never understanding . . . this people’s heart has become calloused.” By quoting Isaiah 6:9-10, Jesus explains that the rejection of his message fulfills prophecy. Matthew often shows how Jesus’ ministry fulfills prophecy, but the other Synoptic writers include a quotation from Isaiah 6 as well. Many in his Jewish audience, especially the religious leaders, are following the pattern of their forefathers in Isaiah’s day. They hear the prophetic message of God, but with hard hearts they refuse to receive it. Those who reject Jesus’ message will continue rejecting and misunderstanding the word of God.

Parables provide a good illustration of Isaiah’s words and the situation among Jesus’ hearers. Because parables contain a picture/story part that explains a spiritual reality, they can obscure understanding for those who refuse to receive the spiritual reality. Many of the Jewish religious leaders physically heard the parables/message of the kingdom, but they did not receive it and failed to understand it. Especially with the parable of the sower, the story part of the parable part was clear enough, but the only ones who received a full explanation of the spiritual reality part were those who sought more understanding from Jesus (“whoever has will be given more”).

Parables, therefore, clarify spiritual realities for those who have good receptive hearts towards Christ (good soil), but they obscure spiritual realities for those who have rejected Jesus and his message. The parable of the sower is a parable about parables and Jesus’ overall kingdom message. This parable not only explains why Jesus’ message was rejected by some of his own people, it also encourages Jesus’ followers to continue to seek Jesus and receive his word with the soil of a good heart. Jesus’ word will bear a great crop through those who receive him and his kingdom message. “He who has ears, let him hear.”

END NOTES

* Barry, John, ed. Lexham Bible Dictionary. Bellingham: Lexham Press, 2016.

*Blomberg, Craig. Interpreting the Parables. Downers Grover: InterVarsity, 1990.

*______. Jesus and the Gospels. Nashville: B&H, 1997.

*DJG: Green, Joel and Scot McKnight, eds. Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels. Downers

Grove: InterVarsity, 1992.

*EDT: Elwell, Walter, ed. Evangelical Dictionary of Theology. 2nd ed. Grand Rapids:

Baker, 2001.

* NDBT: Alexander, T. Desmond, et. al. New Dictionary of Biblical Theology. Downers

Grove: InterVarsity, 2000.

*Stein, Robert. A Basic Guide for Interpreting the Bible. Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 1994.

The Holy Spirit Brings Restoration in the End-Times Renewal

Discussions of the End-Times often center on Jesus’ return. But what role does the Spirit play in the End-Times? Beginning in the Hebrew Scriptures and continuing through the Second Temple period, the Spirit is depicted as the means by which God accomplishes his historical and eschatological plan.[1] That eschatological plan includes an expansion of the Spirit’s work upon the earth as well as the Spirit’s inner work that transforms the hearts of the covenant people.[2] The Spirit’s renewing work would prepare God’s people to experience His presence.

In his sermon at Pentecost, Peter cites the pouring out of the Spirit as evidence that the “last days” have begun (Acts 2). The New Testament writers believed that they were in the “last days” (end times) and these previous promises were being fulfilled. The Spirit would indwell and empower the church to expand God’s kingdom to the ends of the earth until Jesus’ return. This post will point out some first-century expectations concerning the Spirit in the End-Times.

Pouring out the Spirit: Eschatological Expansion

The Old Testament (OT) often portrays the Spirit of God as working in leaders and prophets to establish, deliver, judge, guide, and restore the people of God.[3] Not surprisingly then, the Spirit is also depicted as active among God’s people in the eschatological restoration.[4] The eschatological work of the Spirit increases in scope and intensity. This increase is described as a “pouring out” of the Spirit in many OT passages (Isa 32:15; 44:3; Ezek 36:25–27; 37:14; 39:28–29; Zech 12:9–10) and exemplified by Joel 2:28–31:

It will come about after this that I will pour out my Spirit on all mankind and your sons and daughters will prophesy, your old men will dream dreams, your young men will see visions. Even on the male and female servants I will pour out my Spirit in those days. I will display wonders in the sky and on the earth, blood, fire and columns of smoke. The sun will be turned into darkness and the moon into blood before the great and awesome day of Yahweh comes.

Joel 2:28–31

By twice using the verb שפך (pour out) and the threefold repetition of spiritual gifts in the following lines, Joel expresses a fullness of amount as well as fullness in scope.[5] The Spirit will not only be upon leaders and prophets, but upon all of God’s people. The day of the Lord, with its theophanic imagery, brings a renewal of the covenant presence (Joel 2:27, “Thus you will know that I am in the midst of Israel, and that I am Yahweh your God”) and an expansion of Yahweh’s Spirit among his people. The promise of Yahweh’s restored covenant presence “in the midst of Israel” is closely connected to the Spirit in many prophetic texts (Isa 4:4–6; 59:19–21; Ezek 36:24–28; Hag 2:5–9). These Hebrew texts create an eschatological expectation for an outpouring of Yahweh’s Spirit in conjunction with a renewal of Yahweh’s covenant presence. The pouring out of the Spirit will broaden both the scope and intensity of Yahweh’s blessings.

Many scholars note an eschatological trajectory to the canon that depicts Yahweh’s presence/glory expanding to the ends of the earth. The Spirit would usher in the promised presence of God among his people as “all the earth will be filled with the glory of the Lord” (Num 14:21) in the eschatological age (Isa 6:3; Hab 2:14).[6]

These expectations inform the background to many of the pneumatological promises in the New Testament. Peter quotes the above passage from Joel in his Acts 2 sermon, and claims that this promise is being fulfilled. In the remaining chapters of Acts, the Spirit is poured out into new people groups and expanding throughout the Roman empire. John’s Gospel shows a similar fulfillment in a slightly different way. John the Baptist introduces the promise that Jesus would baptize in the Spirit (John 1:33), and that promise is fulfilled literarily when Jesus breathes the Holy Spirit on his disciples (John 20:21). This impartation of the Holy Spirit is given in the context of Jesus sending his disciples into the world on a mission of redemption and revelation in continuity with Jesus’ own mission.[7] In addition, the disciples serve a representative function for the later, broader messianic community and the blessings/responsibilities (including the indwelling Spirit) of the first disciples are assumed for later disciples.[8] Jesus gives the Spirit to his disciples when the eschatological “hour” (John 4:21–23; 5:25–28; 13:1; 17:1) arrives, thus expanding God’s glory. The expansion of God’s glory through his disciples and beyond is spoken of in John 17:20–22, which states, “Not for these alone do I ask, but also for those who believe in me through their word; so that they may all be one, even as you, Father, are in me and I in you, that they also may be in us, so that the world may believe that you sent me. The glory that you have given me I have given to them, that they may be one, just as we are one.” The sharing of glory that denotes the unified presence of God radiates to future disciples, who will witnesses to the world.

The Spirit’s work of renewing God’s people and expanding God’s glory presence is a crucial part of End-Times fulfillment. While modern Christians often think of the “End-Times” strictly in terms of Jesus’ final return, the New Testament seems to include the entire church age in the “last days”. In these last days, the Spirit’s role is to prepare God’s people, and the whole world, for the Lord’s full and final intervention.

End Notes

[1] Willem VanGemeren and Andrew Abernethy, “The Spirit and the Future: A Canonical Approach,” in Presence, Power and Promise: The Role of the Spirit of God in the Old Testament (ed. David Firth and Paul Wegner; Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2011), 333.

[2] Robin Routledge, “The Spirit and the Future in the Old Testament: Restoration and Renewal,” in Presence, Power and Promise: The Role of the Spirit of God in the Old Testament (ed. David Firth and Paul Wegner; Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2011), 348–349.

[3] Wilf Hildebrandt, An Old Testament Theology of the Spirit of God (Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 1995), 67–150.

[4] Peter R. Ackroyd, Exile and Restoration: A Study of Hebrew Thought of the Sixth Century B.C. (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1968), 177, contends that the prophets Zechariah and Haggai (shortsightedly) considered the post-exilic time as this restoration. The work of the eschatological Spirit was therefore crucial in their depiction of the restoration of the temple in Zech 4:6 and Hag 2:4–5. While I disagree with Ackroyd’s assessment of the prophet’s intentions, the larger point of the Spirit’s work in the promised restoration is still relevant. The Spirit of God transcends the temple and is therefore involved in its restoration.

[5] G. A. Mikre-Selassie points out that Joel often uses repetition to emphasize fullness in “Repetition and Synonyms in the Translation of Joel—With Special Reference to the Amharic Language,” BT 36 (1985): 230–237. See also Douglas Stuart, Hosea–Jonah (WBC 31; Waco: Word, 1987), 260.